|

The “Pizza Wars” episode of “The Food That Built America” airs again tonight on The History Channel at 9:00 CST, and it streams now on its website. The episode focuses on the rivalry between Pizza Hut and Dominos, which are now the two biggest pizza chains in the country, and have been the introduction – and even benchmark – of pizza for a great many folks. I am on the episode a couple of times. It was fun to muse about pizza in front of a camera, at times even more fun than eating it.

0 Comments

Pizza originated in Italy, to be sure, but it is not originally Italian. This is because pizza is specifically Neapolitan in origin. It’s from Naples, the big, chaotic and historic port city in southern Italy, and pizza actually spread more quickly throughout the U.S. than it did elsewhere in Italy, as odd as that may seem. Pizza initially traveled with the immigrants from Naples and its environs, of whom there were many to the U.S. To note, the Sicilian pizza is also fair part the pizza landscape here. Arriving later, it was derived from the sfincione served in Palermo, a type of spongy focaccia, but that’s for another tale.

A brief history of pizza in America until it become popular One of the most important events in the gustatory history of the country seems to have begun officially in 1905 when Gennaro Lombardi, a native of Naples, opened the first licensed pizzeria in America in Manhattan’s Little Italy, Lombardi’s. He had been making versions of this strictly Neapolitan fast food at the bakery in which he worked, which was also being done elsewhere, at least in his neighborhood. The New York Tribune noted a couple of years earlier in 1903 in Little Italy that “apparently the Italian has invented a kind of pie. The ‘pomidore pizza,’ or tomato pie.” These pizza pies were just the province of these Neapolitans; in Italy at the time, it was not found outside of the vicinity of Naples. “There are only two places in New York where you can get real, genuine Neapolitan pizze. One is on Spring Street and one on Grand. The rest are Americanized substitutes,” reported an informed source, “the Dago,” in a Sun piece in the summer of 1905. These pizzas first found an audience with those recently arrived Neapolitans and quickly spread to all the Italians living in the neighborhood. Pizza has proven to be a very easy sell over the years. In the 1920s and 1930s Lombardi’s former employees, all Neapolitans, opened pizzerias in Brooklyn, East Harlem and uptown Manhattan that would be destined to become icons in their own right. But, pizzas were really an ethnic, mostly Italian, specialty until after the Second World War, even in New York City. Also in the 1920s, pizzerias were opened by Neapolitan immigrants in the Italian neighborhoods of New Haven, Connecticut, Trenton, and Boston. Philadelphia and Chicago were two of the few other cities with Neapolitan pizzaioli and pizza before the Depression. Pizza spread throughout the country after the Second World War, as it began to be served well beyond the Italian neighborhoods. Starting and growing in areas with virtually no competition from pizzerias with Italian antecedents, several regional, national and international pizza companies got their start in the mid-1950s to 1960: Shakey’s in Sacramento in 1954 – the name referencing one of its malaria-damaged owners – Pizza Hut in Wichita and Pizza Inn in Dallas in 1958, Little Caesar’s in suburban Detroit in 1959, and Domino’s in Ypsilanti, Michigan in 1960. Commercially made gas and electric pizza ovens, along with large mixers for the dough introduced in the mid-1950s, helped make the creation of the pizzas easier, far less dependent on a seasoned pizza-maker. American business know-how helped even more. The franchise system increased the number of branches and market presence quickly. Even if far from the best pizzas around – the pies usually featured doughier and blander crusts and lower-quality toppings – these pizza chains have been greatly enjoyed by millions over the years. Not incidentally, with tremendous insight, or luck, Pizza Hut, Dominos and Pizza Inn first opened right near colleges and universities whose enrollment grew tremendously from the 1950s on, something that these chain pizza joints rode to continued and continuing success. An even briefer history of pizza in Italy outside of Naples “Pizza, which was unknown in north Italy before the war” recounted cookbook author Marcella Hazan in her memoir Amacord. Pizzas was difficult to find anywhere outside of the Naples region through the 1950s. Even in southern Italy beyond the greater Naples area, it was not be found. A family friend from Reggio Calabria, the city at the toe of the boot, did not have her first pizza until she arrived in New York in the late 1950s. She said that Naples was the only place in Italy to get pizza then. It came to those other cities with transplanted Neapolitans who traveled north to find work in the industrial boom after the war. For example, in Hazan’s northern region, Parma, a well-to-do and university city, got its first pizzeria in 1960 started by a person from Salerno, south of Naples. Though now popular throughout Italy, pizza has taken hold the most in a city closer to Naples, Rome, which has developed a couple distinctive versions. The first was pizza tonda, a round pizza with a blistered cracker-thin crust that grew out of the Neapolitan versions. Then came pizza al taglio, a long rectangular pizza without Neapolitan antecedents, which is more like a focaccia and sold mostly in take-away places. It has become synonymous with Roman pizza outside of Rome. The Eternal City also currently boasts some excellent pizzerias making version similar to those in Naples. It is true what Carol Helotsky wrote in her book Pizza - A Global History: “Pizza went from being strictly Neapolitan to being Italian-American and then becoming Italian,” though I’d clarify, adding that it became American after Italian-American. Brandi in Naples, the birthplace of the margherita pizza, and the home of the best margherita pizza I've ever eaten.

Some years ago, a longtime friend who is an avid cook, asked me if my family had a good recipe for meat sauce. I responded no, a little surprised with the question, as I think that we had it at home when I was a kid, though I don’t have any memories of it. And, these days, it’s not something that I make very often at all. But, meat sauce with spaghetti used to be seen on just about every Italian-themed restaurant menu in this country and is still to be found. It can be quite satisfying if done well, to be sure.

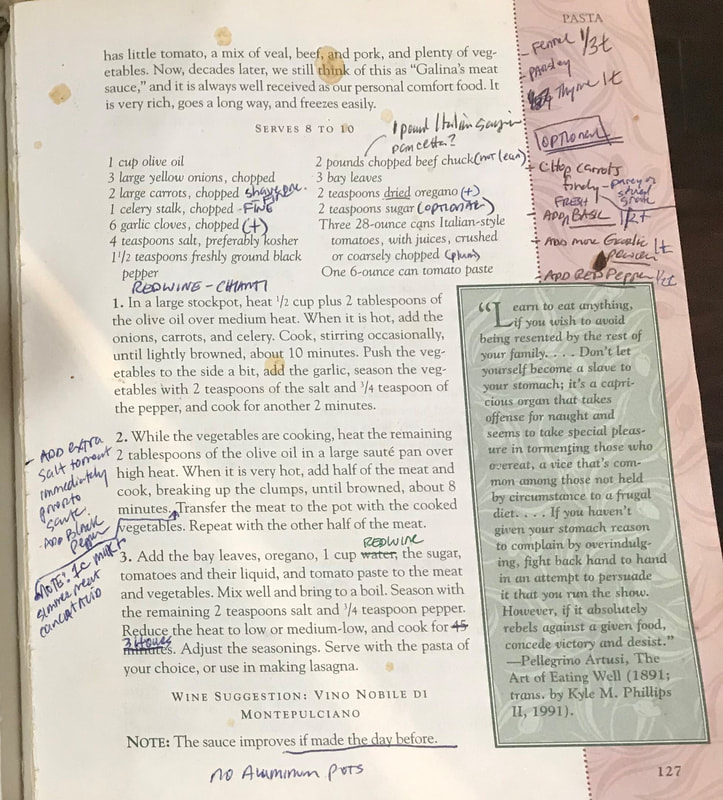

This Italian-American meat sauce is distinct from the famed and delicious ragù Bolognese that’s typically served with wide strands of freshly made pasta and originally comes from Bologna, the capital of the rich-food region of Emilia-Romagna. The main reason is that hardly any of the Italian immigrants came here from that area. Also, it’s made differently than what is called meat sauce. True ragù Bolognese was almost unknown on restaurant menus until the mid-1970s with the introduction of “Northern” Italian cooking to the U.S. that included Marcella Hazan’s inaugural cookbook. This had a terrific recipe for the dish, which gained a lot of traction among adventurous home cooks. Meat sauce is also not what Italian-Americans often call “gravy” or “Sunday gravy,” a very long-cooked sauce featuring several types of meat that comes from the Naples area. Prompted by my friend’s query, I did some research into the origin of the Italian-American meat sauce. From what I found and as far as I can tell, it is typically just ground beef sauteed until done with a little onion or garlic, or both, and then added to a cooked tomato sauce. It is easy with tomato sauce on hand, better homemade even pulled from the freezer on a weekday night. Something much tastier is a preparation that my brother and his wife have been making for years. Soon after it was published in 2000, my brother and I had copies of The Italian-American Cookbook by John Mariani, the longtime food and restaurant writer, and his wife Galina, a book that seemed to fit quite well how we liked to eat and cook. John Mariani happened to be part of the small group along with me on a gastronomic trip to Pavia near Milan in late 2019. I had to quickly tell him that my brother and sister-in-law were big fans Galina’s Meat Sauce (page 126-127) – as I was of their efforts – though they ended up modifying the recipe in his cookbook. He seemed quite pleased, though I couldn’t tell if he minded the desire for changes to it. Mariani mentioned that the meat sauce was entirely Galina’s creation, bay leaves weren’t part of his mother’s Neapolitan-rooted cooking, and has been a favorite of his and his sons for years. I can see why. The adjustments that Gene and Cara made gave the sauce a little more complexity and richness. They added milk, additional dried spices – fennel, parsley and thyme – replaced the water with wine, seasoned the ground beef when it was cooking separately, omitted the sugar, and simmered the sauce for three hours instead of forty-five minutes. It was now not too unlike a ragù Bolognese, if with still the familiar Italian-American taste. You might want to give this a try when you have a few hours to cook. Cara’s and Gene’s version of Galina’s Meat Sauce – Not the most elegant name, but I couldn’t come up with anything better. Ingredients Olive oil – 1 cup Yellow Onions – 3, chopped Carrots – 2, grated Celery stalk – 1, finely chopped Garlic cloves – 6, minced Ground Beef – 2 pounds; alternatively, 1 pound each of ground beef and ground Italian sausage Milk – 1 cup Red Wine, dry – 1 cup Peeled Tomatoes – 3 28-ounces cans Tomato Paste – 1 6-ounce can Bay Leaves – 3 Oregano, dried – 2 teaspoons Fennel, dried – ¼ teaspoon Thyme, dried – ¼ teaspoon Parsley, dried – 1 teaspoon Salt – 5 teaspoons Black Pepper – 1 teaspoon Directions

I’ve made this sauce, albeit without the fennel seeds, which I don’t usually have. It was still excellent. It is better the next day as the Marianis mention, and it freezes very well, too. The very well-used cookbook

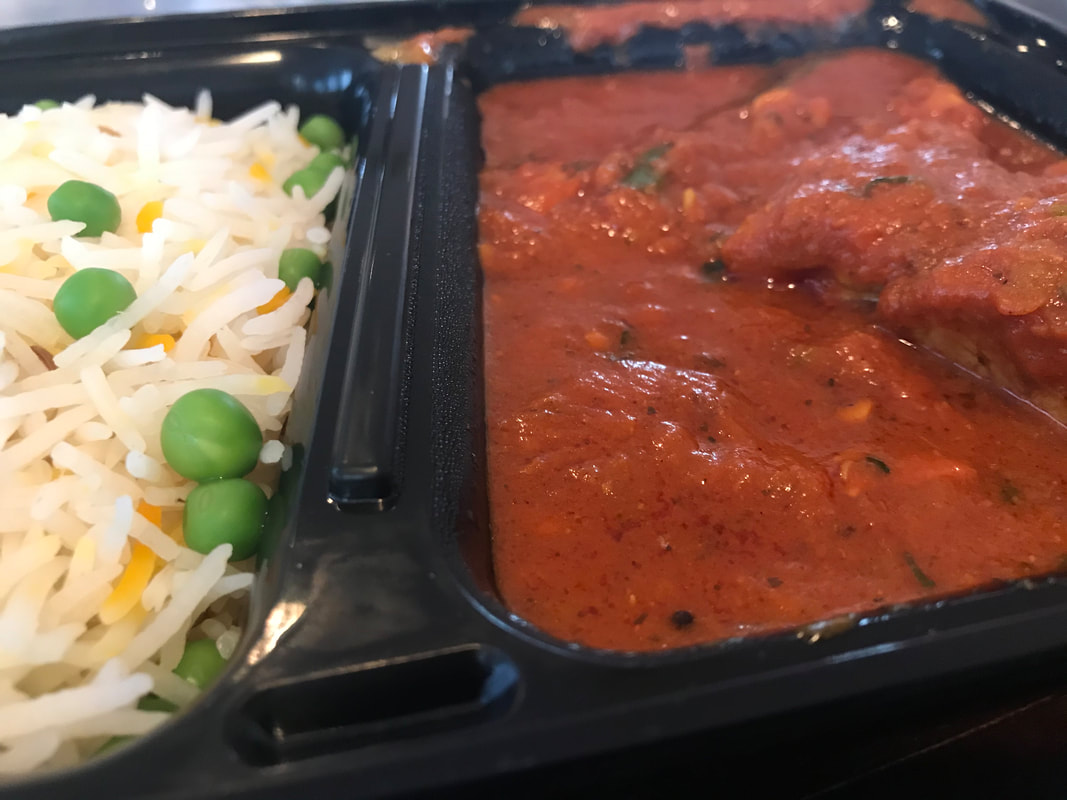

The smart, smallish storefront Indian restaurant on Durham not far south of Washington has been a regular stop for me since the pandemic began. Convenient, even though I have to briefly enter the restaurant, a trip to pick up a meal is always quick, as the order is ready and the checkout is swift. The food travels very well back home to consume, much better than from most places. Surya was a regular stop for me before the pandemic began, mostly because I really enjoy the food.

I’ve really enjoyed pretty much everything there, and I’ve had, or nearly had, every entrée. After ordering it more than a few times now, I have to finally admit that my favorite preparation is the Chicken Vindaloo, which I had once again the other day and edges out their version with lamb for me. This Goan-originated dish was properly spicy, actually extremely spicy this last time – three glasses of water and a half-glass of milk were necessary to get through this lunch – but more significant was the deep flavor of the reddish-orange-colored sauce with an enjoyable brightness, richness and complexity that I could barely pause from, ladling it on the terrific long-grain rice side or scooping it up with the soft, occasionally blistered fresh naan. Studded with moist pieces of white chicken meat that are actually quite savory and cubes of soft potatoes, this is a delicious meal. A visit to Surya, especially for the vindaloo, is one of things that helps makes these times more bearable. Surya 700 Durham (a couple of blocks south of Washington), 77007 (713) 864-6667 suryahouston.com |

AuthorMike Riccetti is a longtime Houston-based food writer and former editor for Zagat, and not incidentally the author of three editions of Houston Dining on the Cheap. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed